Governance: a perspective on monopolies and competition

In a free-market economy, a central tenet is that competition will enable the emergence of a balance of power between producers and consumers. If a producer keeps their prices too high, produces substandard products, or engages in practices that consumers generally disapprove of, then consumers have the freedom to move to a competitor that will seize this opportunity. As a result, the inefficient or abusive producer will be either pushed out of the market or forced to adapt. The theoretical benefit of this dynamic is optimal price adjustment, a push for innovation, and an asymptotic alignment with consumer values. This, of course, relies on at least two crucial assumptions that are not met in the general case:

- There is a choice of producers available (no monopoly).

- The cost of switching to a new producer is acceptable to the consumer (it costs less than the loss due to the current inefficient situation, or it can be amortized over long periods).

On certain types of markets, economies of scale can make it impossible to compete with the dominant player, and dominant players will tend to acquire smaller potential competitors to maintain their position, or lobby the centralized government to enforce regulations that favor them over new entrants. So it is hard to imagine that we can avoid dealing with the first point. Monopolies cannot always be overthrown by nimble startups, even in a perfectly fluid market.

Traditionally, this problem is dealt with through anti-monopoly laws and occasional government intervention to forcefully break monopolistic entities into smaller parts. However, this approach is far from perfect. First, it is a highly centralized, arbitrary, and politicized process, especially regarding the "why," "when," and "how" to split a monopoly. From a more principled perspective, one can also question the legitimacy of such a split, as it effectively amounts to a forceful disruption of private property for the shareholders. Another issue is that not all monopolies are entirely detrimental to customers: the economies of scale and rationalization of mass production can translate into better and cheaper products, and greater capacity to invest and innovate, depending on the orientation of management toward short-term vs long-term goals. It seems that sometimes the cure can be worse than the problem. But still, there is a problem.

If we look more carefully, there is an interesting parallel to make here with governance problems in general. The reason why monopolies are generally bad is not really that the customer cannot move to a competitor, but rather that they have no say in the governance (unless they are shareholders). Opting out and moving to a competitor is in fact a simple signal used as part of an indirect governance mechanism (also known as "voting with your wallet"). Therefore, the lack of competition makes it impossible to express any kind of governance feedback at all. So, if the monopoly makes decisions that are against the will of the customers, they have no way to defend themselves. I would argue that ultimately in the case of a monopolistic situation, what consumers complain about is not that there is a monopoly, but that they have no say in how it is governed. In any case, the ability to move to a competitor when this is possible should be seen as a last resort option for governance, because it is a very crude and one-way signal.

The logical solution could be that if you are unable to switch away from a particular producer either because of point 1 (monopoly) or point 2 (switching costs), then you should somehow have a voice in the governance of this producer, at least as long as you are one of its clients. The first difficulty with this idea comes from the measurement of the monopolistic situation: in realistic cases, you are often never in a pure monopoly case, and switching costs are also not just zero or one. What seems more appropriate is to consider a sort of continuum between zero (absolute freedom to switch) and one (absolute locking). We will discuss later how we could better formalize this notion. The second difficulty is related to the notion of "being a client". If one buys a washing machine and then resells it to somebody else, how could we track who is a client and when? Couldn't competitors game the system by doing large bulk buying of products to influence the governance of their opponents?

There is one technology that is especially well-suited to address these issues, and also supports a trustable infrastructure to track client voting rights: the blockchain. Actually, I believe that governance applications are the most important and legitimate applications for blockchain technology overall, well ahead of DeFi or even token-as-money applications that got most of the attention so far. Governance is a core issue for any organization, and has traditionally been handled in a centralized way, making it prone to manipulation, corruption, etc. It is especially interesting to observe that in most cases, the exercise of governance rights is orchestrated and coordinated by processes under the direct control of those who have a stake in the outcome of the governance results. It is fundamentally equivalent to saying: "I trust you that the tools you gave me to remove you from power are not rigged". In the case of company governance, one should be skeptical of any voting system given to the customers that would be centralized and controlled by the management, whose fate could be affected by the result of the votes. The blockchain is a much better and neutral platform to operate these kinds of voting rights, based on cryptographically secure protocols. Note that, on the decentralization issue, not all blockchains are equal. Many blockchains advertised today as "decentralized" are in fact more or less subtly centralized with very low Nakamoto coefficients (this is the number of entities you need to effectively control/corrupt in order to take control of the chain). In that regard, I would personally favor solutions like the Massa blockchain, which has focused all its development and policies around the obsession over decentralization, realizing a Nakamoto coefficient of more than 1000.

Going back to the question of tracking clients voting rights based on their purchase history, a blockchain solution using a properly decentralized protocol would allow one to record who has bought what at the time of purchase. More precisely, you would be able to hand a public key to register your purchase, this key being totally anonymous as to minimize any risk of privacy violation or tracking. Tokens would be attributed when the purchase is made. As always with token-based governance, it is very complicated to make it work in practice. For example, here are some of the characteristics of the token that should be considered to counter potential abuses to some extent:

- The token has a limited life time. What matters is whether you are currently a client of the company. We shouldn't care if you did purchase something 10 years ago. So, voting rights could decay progressively over time, or simply go from 1 to 0 after a certain time limit. The progressive version is preferable to an abrupt end to avoid deadline effects, but this is a detail.

- The number of tokens attributed is proportional to the amount of purchase you do. This is a simple principle that avoids issues with Sybil attacks, as splitting orders over multiple wallets would become useless.

- The token is not transferable: this avoids the obvious pitfall of people selling their token on secondary markets. You could still of course sell your private key in some kind of black market, and people could still buy your vote, but this is more complicated to do, and it could in principle be made illegal (which would not make it impossible of course, but would greatly limit the impact).

Regarding the voting mechanism itself, and what exactly people can vote for, when, and who can propose votes on the agenda: this is a whole subject of study and I will not dive into it deeply here, as there has been entire books devoted to it (as an intro, see this article by Vitalik Buterin). What matters here is that there is a way to share governance with the shareholders, and the details would have to be defined and refined over time.

However, just to illustrate the richness of the possibilities let me mention one interesting option which is called "Conviction Voting". In a nutshell, the idea is that potential decisions to vote are put on the agenda and people can "commit" their voting token to some of them, with the property that a committed vote acquires voting weight over time, within some limit. This means that there is a cost to changing your vote distribution, and a reward for standing by your convictions. The voting power of the committed token would increase over time, but uncommitted token would instead decrease in voting power in agreement with the "limited life time" property discussed as a requirement to capture the temporary nature of "customership". The decrease would virtually continue to happen in the background for any committed token, so that if you uncommit it, its voting power would be the one you would have had at that time if you did not commit it before. In particular, uncommitting a very old token would certainly make it disappear instantly, since it would be well past its due time. But as long as it remains committed, it gains in voting weight, up to some limit. As more people commit tokens to a particular decision, and as voting weights of committed token increase, so does the total committed voting power for the corresponding decision, which simply sums all individual committed token weight. If a threshold is met, the decision can be passed, or the corresponding policy applied as long as the threshold is maintained. One of the benefits of conviction voting is that it makes vote buying much less effective. You have a time penalty. It also allows to reward small but very committed communities by recognizing the strength of their opinion over time.

As I said, there are many more voting systems that are studied in the broader field of DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) within the blockchain ecosystem, like quadratic voting, holographic voting, delegation, reputation-based systems, etc. I find "conviction voting" particularly interesting in the context of customer-centric company governance, but more creative solutions could be designed since we are here in a purely computational context, which is much easier to adapt than any physical voting system.

So, let's assume, for now, that we have somehow set up a proper technical stack that would allow customers of a company to express their preference for certain decisions (even submit new decisions), enjoy a limited-time voting right that is renewed as they purchase more products from the company and which effectively give them a share of the governance process. Now let's talk about the elephant in the room: why would any dominant monopolistic company surrender some of its governance and risk to allow for some decisions to be taken in favor of its customers rather than in its own interests? Of course, any company is interested in customer feedback, and is actually usually spending quite a lot in customer surveys and other focus groups, etc. But these are consultative methods, not performative as a vote would be.

Again, we can look at the problem from a more general governance framework perspective. In the absence of a direct customer governance mechanism, as we said before, it is traditionally the role of governments to intervene in order to mitigate abuses, set up regulations and in general try to express the voice of the general interest, which is, in theory, why they are elected for in the first place. In other words, they act as the armed wing of customers, but in a very indirect way. It is a very imperfect association because it is clear that Coca-Cola customers did not vote on the last presidential election directly thinking about how their newly elected politicians would interfere with Coca-Cola's business in order to improve the quality of their drinks. But still, as imperfect as it is, this is a form of indirect governance. The cost of this government service is financed via taxes, just like any other government activity. This suggests to a possible agreement with companies in monopolistic positions that might look like this: "we could reduce a certain part of your corporate taxes in proportion to the amount of governance you surrender to your customers". Effectively, the government would offer a tax cut equivalent to the cost of acting as an indirect governance operator for customers, if the customers are in position to exert this governance directly.

Less tax means more profit and more return to shareholders, so the deal could make sense for companies, even if the fact of allowing for some customer-driven decisions could reduce the company profit in the short term. For companies that are not monopolies, the tax deduction should be automatically applied to some extent even in the absence of a customer governance sharing, since the ability to opt out and switch to the competition is a form of governance already. It goes without saying that the acceptance of a tax revenue reduction from the government would not be an easy thing to achieve. But in theory, if the government were to act in the benefit of the people as they should, and following the above reasoning, there should be no problem with it because the tax cut would go hand in hand with a spending cut, reducing the size of various regulating and monitoring agencies, inspectors, auditors, etc.

The fine tuning of the size of the tax cut offered here would involve a measure of the level of monopolistic status for each company, and the level of customer governance sharing. This brings us back to the question of how to quantify the monopolistic level of any given company. The first difficulty comes from the fact that a company can be a monopoly on certain types of products and not on others. Reducing the monopolistic status to a single variable, instead of a vector, is a big simplification. But we can convince ourselves that it's not so far off, since distribution, marketing or logistic advantages from one dominant position on a product will in general translate to other products as well. Besides, implementing a form of "company" x "product" governance token matrix would probably be too complex to handle for the users anyway (even a single token per company will pose some serious UX challenges). To simplify, in the following we can imagine tracking, defining and evaluating the monopolistic status of a given company for each of its products, but we would then take the average over all those products to end up with a single number between 0 and 1 per company.

Now, let's assume for the sake of argument that the system we discuss here becomes popular and that almost all companies somehow distribute tokens to their customers, in proportion to how much they buy. One relatively objective measure we could imagine to establish how much a company is monopolistic with regard to a given product is simply to evaluate the ratio of its currently distributed and active tokens versus the sum of all the other tokens from other companies for similar products. This supposes a form of rational classification of products, in order to automate this on the blockchain by comparing token product ids. It is not easy but doable, and already existing for logistics and accounting purposes anyway. Note that there would certainly be a bootstrap phase, but given the proper incentives for tokenization arising from the potential tax reduction we talked about, one can imagine that many companies would soon adopt the token-based approach for their products.

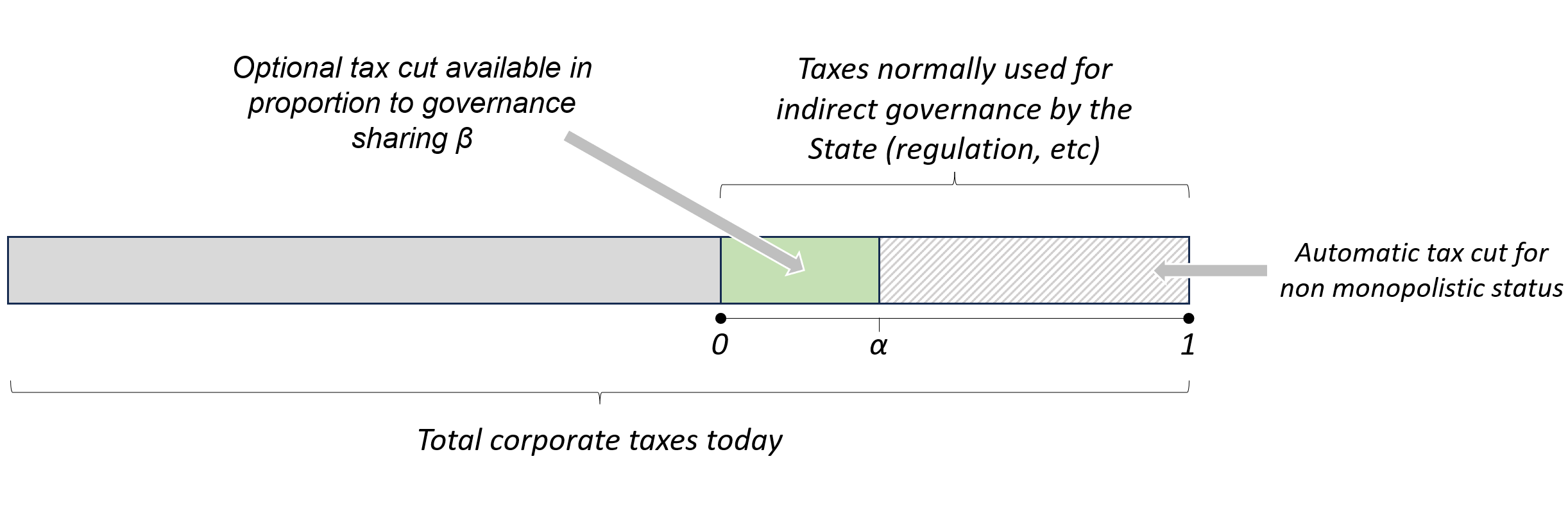

Let's call this monopolistic coefficient \(\alpha\). Fundamentally, it represents the percentage of the tax deduction share available to the corresponding business, if it were to implement a fully user-controlled governance. Visually, it would look like this:

Note that the tax deduction share is not 100% of the corporate tax, just a subpart that corresponds to the estimated amount that the state need to pay for its service as a regulator, acting as an indirect governance body. It is hard to say how much this could be, but it would have to be substantial to incentivize companies to consider the option.

Now, of course the company is not forced to implement a full user-controlled governance (probably none would do so), so the effective tax cut applied in the green area above would linearly depend on the level \(\beta\) of shareholder governance surrendered to customers with governance tokens, leading to a practical coefficient of \(\alpha\cdot\beta\) regarding the amount of tax cut on the portion of taxes devoted to governance.

The technical specifics here could greatly vary, this is merely the simplest model we can start with. The core idea remaining that the more monopolistic a company is, the more it is incentivized to share its shareholder governance with customers, in order to reduce its taxes. Smaller competitors, with a small \(\alpha\) would automatically benefit from a substantial tax rebate (the green area below would be small and the dashed area would cover most of the potential tax cut), which would help them to better compete against the monopolistic company. All this would happen in a fluid way with several benefits:

- Natural balancing of the monopolistic force without the need for an arbitrary centralized state decision.

- Opportunity for consumers to influence directly the products they use, in proportion to how much they are locked in with them.

- Potential benefits for the monopolistic companies: avoid costly legal actions to defend their integrity. Allow to reduce their tax level. Gain direct and rich feedback from their customer base.

Quite clearly, this ambitious program would not be easy to set up in practice. One can list several issues already:

- Designing a proper token-based voting system, or at least a toolkit for companies to chose from, so that it is not biased, not easy to abuse, preserve privacy, etc.

- Convince governments to surrender part of their tax revenue, and adapt the tax model of companies to information available on a blockchain.

- Integrate this within the framework of international tax optimization. Most monopolistic companies are already reducing their tax bill by optimizing their international structure and offloading their taxable revenues to low tax jurisdictions. Tax reduction being the main drive here, there should be taxes to reduce in the first place...

- Provide a user experience that is smooth and friendly, so that it gets adopted by customers. Solve the problem of voting incentives (most DAOs have very low level of participation as for now).

- Integrate the blockchain and the token attribution mechanism into the payment infrastructure of shops, online seller, etc.

- Fighting black market platforms for vote selling or private key selling.

Obviously the devil is in the details and this short brainstorm is by no means a precise plan for action, but rather a source of inspiration. It illustrates the potential of using the blockchain as a tool to distribute more power and more control directly to stakeholders without the need for a centralized (potentially corruptible, unfair or ideologically biased) intermediary. It also proposes a way to smooth the old dichotomy between competitive markets and monopolistic markets by presenting it as a continuum that does not need clear cut boundaries, but simply adapts to best serve the interests of all parties. In that sense, it can serve as a source of idea to try to implement a fully decentralized capitalist economy, where suboptimal (and unavoidable) monopolistic local minima are dealt with from within, without the intervention of the State.